There is also a life before death …

An interview with Lydia Gastroph, owner of the label to promote mortality and life culture w e i s s über den tod hinaus

Text: Paulina Tsvetanova

Dear Lydia, you curate and sell artfully-designed urns and coffins created by recognized and aspiring artisans and designers. A very unconventional, innovative job! It’s no surprise you lectured as a founder at the annual Entrepreneurship Summit. Is your job your calling?

Dear Paulina. Yes, in my company w e i s s über den tod hinaus I sell caskets, urns and funeral jewelry designed and hand-crafted by renowned artists. I also curate exhibitions on the theme of “Farewell Art” in galleries, hospices, churches and other beautiful or unusual places. I created a “coffin shop” as a pop up store in downtown Munich. Due to popular demand of my customers, I have also started to work as an undertaker. I put all of my strength, my stamina, my enthusiasm, endless time, energy, motivation and love into this company. It is my calling, my passion.

Lydia Gastroph, Photo: Miriam Künzli

Your company seeks to destigmatize the subjects of death, farewell, dying. In Germany as in other affluent societies, this subject is unfortunately very repressed and uncomfortable. Nowadays we do everything possible to us to optimize our longevity and even to bypass death, to prevent it or to age backwards. Why? Death is actually quite normal and part of life. Did your company emerge from a deep desire for social rethinking, or was there a more personal reason?

Fundamentally, I try to scrutinize and re-think the status quo: must things be as they are? Are there ways to embellish something to improve it, to humanize it, to make it sustainable and environmentally friendly? And I’m ready for radical social rethinking. It requires courage, to confront the taboo subject of death and set out to deal with such extreme experiences. As a young girl, I was deeply touched by the death of my classmate, who died at age 17 from leukemia. At her funeral I felt that the old-fashioned, heavy, and massive coffin did not suit her. At other funerals later on, I often wondered at what I saw there, whether everything really must be so bleak, and whether a coffin must be so industrially-manufactured. The key experience establishing my company was my sister’s diagnosis with terminal cancer. With this, a process of profound personal confrontation with dying, death and goodbye was set in motion. My sister wanted to create her last farewell herself and I wanted to do something beautiful for her, a final kindness, so to speak. So I made it my goal to oppose the aesthetic and artististic deficit in our culture of grief, which I had long perceived, and to replace it with a culture of grief which is aesthetic, artistic and individual.

- A variety of urns in Lydia Gastroph’s reception room

- Large red coffin from Lene Jünger, used also as a cabinet

Your “products” are funerary art that can be used even in life, as a chest, box, cabinet, bench, etc. Is the multi-functionality of simple modern vessels a deliberate or conscious choice? Do you think that by integrating these objects into daily life, customers will not be put off by the “original function” of the vessels?

I place a great importance on the aesthetics, beauty and the high-quality artistic and craftsmanship of these “last things”. Our brain responds to unpleasant visual stimuli with fear and rejection. This is why I consider it wise to oppose the inconceivability of death with conscious, artistic design. Since my products can be easily integrated into a modern residential environment, both the coffins as furniture pieces, and the urns as vases or vessels, we have the opportunity to deal with death, which can enter our lives at any time, on a daily basis. From a pragmatic point of view, the multifunctionality of objects is useful both from the ecological as well as the economic point of view. If we consider that every single one of us has to be buried or burned by law in a coffin, it is certainly sensible to use it as a cabinet or chest in our lifetime.

-

- Urn “In Your Hands” by Kati Jünger

Many young, healthy, living people buy such urns and coffins and put them in the living room. Isn’t that a little spooky? Do you think they like to deal with the issues of one’s own transience, the incomprehensible and the uncontrollable on an artistic level?

My experience in dealing with these “last things” has shown that these products encourage people to think and to feel relief, finally, to ask questions and communicate in a quite uninhibited way about the topic of death. People who want to deliberately prepare their burial have told me that it is soothing to know their last dwelling. It also opens the way to talk with relatives and friends about dying, death and burial, and to formulate wishes for their own farewell. Guests and friends who visit me at home are amazed at how beautiful this can look and how unproblematic it feels to live among the innumerable coffins and urns that populate my home. No one is creeped out by the coffin-cabinet which stands in my living room, on the contrary, it often inspires imitators. One can easily understand this: death belongs to life.

Farewell Art: Large red coffin and flower decoration from the Flower Art School Weihenstephan

Unique, individual coffins and urns are part of the “artistic staging of death”. And isn’t this a pious thing from a Christian point of view?

To care for myself and for others, to bring love and appreciation to myself and my fellow human beings is a Christian commandment. This commandment does not end a person’s death. Individual design of the “last things” is like a final act of love. To want to give someone something special on his or her “last journey” is an expression of deep appreciation. Two years ago, I converted to the Catholic faith, not least of all because I am attracted and fascinated by artistically-designed churches. Would these spaces then also be irreverent from the Christian point of view?

Ruth, Lydia Gastroph’s deceased sister, in a coffin store She was the great, decisive inspiration w e i i s s über den tod hinaus

Your customers certainly attach great importance to aesthetic design, sustainability and ethical values. While it can’t bring the deceased back to life, but it lightly softens and embellishes the grief. How would you describe your customers?

My customers are mostly people who have dealt with art, culture and design, or come from this professional environment, and want to be buried as they have lived. Many came first from my artistic circle of friends. They were thrilled that I could offer something that suited their views and their lifestyle. Now they had the opportunity to escape the “optical horror of burials” – as they called it. Others were looking for new forms of farewell design over the Internet, or attended one of my exhibitions and lectures.

Urn Burial, Farewell to Rhino

Why did you also feel that you should work as a death-companion and undertaker? Is the artistic conception of a funeral enough, or do you consider these services equally indispensable?

I am not a trained death-companion, but I accompany my clients, at their request, up until the end of their journey beyond death. I mainly act as an artistic funeral consultant, and an encouragement to take initiative with regards to the design of their final farewell. I would like to take away people’s fear of shaping and carrying out the final farewell. In this area, too, we can develop into mature citizens who are self-determined and well-informed, capable of putting your wishes into practice. The deep-rooted presumptions of our society haven’t lost much ground. What is nice is that I can now access a large artistic network that I have built up over the years and which can be made available to my clients.

-

- Urn in the making – in the workshop of Kati Jünger

You invite musicians and writers to some burials, where they create a burial as an unforgettable performance. What a beautiful appraisal of the deceased. So you place great emphasis on your rituals being different from the traditional. What is played, read, sung?

Rituals are culturally-integrated actions that make sense of things and provide support and guidance. I do not want to give in to trends, or to be flippant with the idea of ritual. Rituals emerge over long periods of time and have a deep meaning. Christian rituals, for example, give comfort through faith in resurrection. As part of a farewell gathering, I try to motivate the family members and the circle of friends to recite or perform something themselves. I make recommendations: music, which is played live, actors to read lyric or literary lectures, for example, one might read a poem by Robert Gernhardt. Dance, or even fairy tales, which are symbolic life-cycle stories. All this is carried out at the highest artistic level. It is important to be able to oppose the cookie-cutter “assembly line music” with live music – and especially the new and unpredictable, never before heard, composed specially for the occasion. I offer to people who want to plan their own funeral, to listen to music from the musicians who will later play at their burial. I once experienced a very moving live performance at the grave with the favorite songs “Strong as Two” by Udo Lindenberg and “Just to visit” from the Toten Hosen. The client could listen both as often as she wanted up until her death.

- Coffin Interior: Tie Cross by Bea Grawe

- Coffin Interior: The Way of the Flowers by Bea Grawe, photo: Özen Gider

What is the biggest challenge in your job? Perhaps you would like to tell us an unforgettable situation from your professional life.

Probably sounds strange now, but the biggest challenge for me is to write bills for my services because I live from the death of other people. This always leaves me with a bad feeling, because my relationship with clients in this very personal, even intimate, situation is usually very intense, because it is difficult for me to draw the line between friendship and business. There have been many unforgettable situations. Many of them are too private to recount. I often think of how the white-tiled pathology of a hospital is suddenly transformed into an almost contemplative, spiritual place, thanks to the special charisma of one of our coffins. One of our terminal clients had us deliver his red coffin to the unused pool of his bungalow and photographed us enthusiastically. Just as my dying sister asked me one evening, to arrange her coffin interior, hand-felted for her personally by a textile artist, and her burial clothes, which she had arranged herself, before her sick bed.She remarked “Lovely, I like it. I am happy. You don’t need to put it away anymore” then, she sent me home. The next morning she died.

- Farewell to the Rhin

Do you try to alleviate the fear of death in your clients and your collaborators?

No, that would be presumptuous. A person can manage the fear of death only for his or herself. However, I believe that the struggle and the daily thought of death contribute to life’s wisdom.

Hermann Hesse said, “All art comes from the fear of death.” What is your personal relationship to death?

Fear of death compels me to deal with death and dying on an artistic level. I am fascinated by the border experiences that are reflected in art. Fear of death urges me to confrontation, not repression, in effect, according to the motto: “He who does not put himself into danger perishes in it.

-

- Deathbed Photo, Collage by Özen Gider, Coffin Interior by Bea Grawe

Do you know how you would like your own burial to be?

Iknow the principal thing – who will bury me. I often talk about it and hope that some of my desires fall on fertile ground. It is more important to me, however, that I die as I hope not suddenly and unpreparedly, but quite deliberately but painlessly and in the hospice of my choice, somewhere where I already have friends and close contacts, and I hope that there is at least one human being to accompany me beyond death, for whom, so to speak, the clocks stand still, someone who has all the time in the world and does not have to go to work or to other obligations. I have already have my coffin-cabinet at home — you just have to lie it flat and remove the shelves, then I would like to be laid out in it openly. If I were to die now, I would like a religious funeral with the priest of my choice, who I know would find the right words. My artistic network will surely make a nice unconventional contribution to the farewell party. It can be quietly romantic, it can be tearful, it can be sad and dark, and anyone will be welcome. Then, to restore everyone afterwards, there should be a funeral banquet so lush and excellent that the tables bend under its weight. My greatest wish is that all of this happens without a employing the services of a funeral home, I want it to be a community project of my relatives and friends. Let me tell you, you can do it!

How do you find the strength to prevent the pain of the deceased their relatives from impacting you personally? Can you have compassion and mourning without sympathy?

My greatest sources of energy are silence and nature. I discovered a couple of nearby places where I can retreat when I need to gather my strength. When I’m alone there and can sink into the here and now, worldly pain, grief, compassion, compassion and self-compassion relativize themselves. If I can not drive out into nature, I search for churches, mostly architecturally modern, which do not distract from inward reflection. In addition, I regularly go to church on Sundays, which structures my work week and makes me pause, gives me comfort and lets me reflect on what is. I feel secure and welcome in a larger community. And I go as often as possible to my adopted homeland of Greece, where I can always find new strength — the light there heals all sorrow.

-

- Sympathy Vase, porcelain from Elisabeth Klein, flowers from Anna Lindner

What is the greatest consolation for the people who know that are about to die? And for their relatives? What can a living person learn from death?

I heard Heini Staudinger give a wonderful lecture on this topic at the Entrepreneurship Summit. Like him, I would like to quote Rilke on this difficult question: “And when I go out of my garden in the evening, I am tired, I know: all the ways lead to the arsenal of the unlived things.” Staudinger interprets this as follows: An arsenal is a weapon room. When it is more and more filled with our own unlived life, our personal arsenals fill up with more and more aggression against ourselves, against the environment and against fellow human beings. What we can learn from death is to live our lives in mindfulness and not to suppress our finitude, but to consciously accept it.

- Urn-vase by Kati Jünger, flowers by Anna Lindner

Have you experienced any miracles? Someone prepared to die who then regained health instead, so everything was in vain?

No, but I hope I can still experience it.

And what about life after death?

If there is a life after death.

- Skull bracelet by Constanze Schreiber, photo: Özen Gider

- Mourning jewelry brooch by Isabel Dammermann

Actually, you are goldsmith and jewelry is your main area of success. Do you also make so-called mourning jewelry? How is it different from normal jewelry?

Around the turn of the century, mourning jewelry was an independent category of jewelry. I myself used to try to work with grief and loss, and to see whether I can handle these feelings in jewelry. And I’ve had success with this approach. Mountain crystal tears, which can be worn as earrings, and the like. For me, the medium of jewelry was never really suitable to combine with the subject of grief, although I now also exhibit contemporary jewelry artists who are intensively engaged in themes such as transience, morbidity, vanitas motifs and the like. From these two professional poles it has arisen that I have told my enterprise of Victor Hugo’s quotation: “Death and beauty are two profound things which carry shadow and light in equal measures, as they are two sisters, terrible and creative at the same time. Protecting the same puzzle and the same mystery.

-

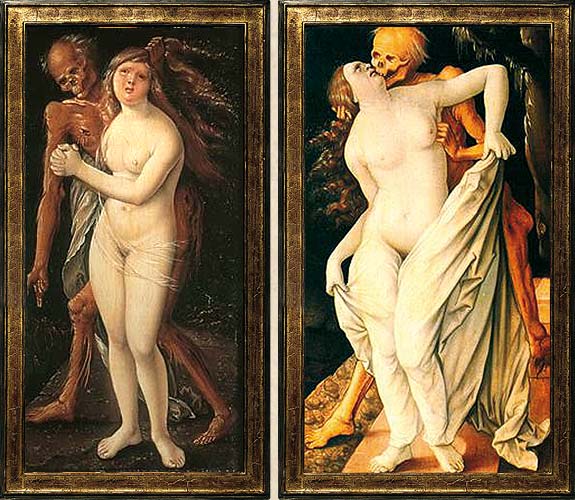

- Hans Baldung Grien, Death and Woman, 1517. As a persecutor, lover, and warning with the hourglass, death appears in Baldung’s pictures. As a contrast to the woman’s flowering beauty, and also because she gives birth to life.

What advice would you give young start-ups?

I would like to say from the heart, be very certain that your founding idea and what you are doing is coherent with and affected by who you are as a person. Today so much has become interchangeable. The virtual world is increasingly withdrawn from the deep human longings for closeness, security and mutual care. The central longing of all human beings, however, is to be touched and touched, not only physically, but, above all, internally. Do not neglect this aspect, because these are the basic needs of your future clients. Do what you do with love and: learn a craft art.

Dear Lydia, thank you very much for this wonderful interview!

w e i s s über den tod hinaus is prsent @ PAULINA’S FRIENDS in BIKINI BERLIN.

-

- Photo of a coffin store, still-lifes on the wall by Eva Jünger, Urn vases from Kati Jünger